Mosquitoes carry more malaria parasites depending on when they bite

When a malaria-infected bird is bitten by mosquitoes over the course of 3 hours, the first insects to feed end up carrying fewer malaria parasites than those that feed later – and the same may apply when infected people are bitten.

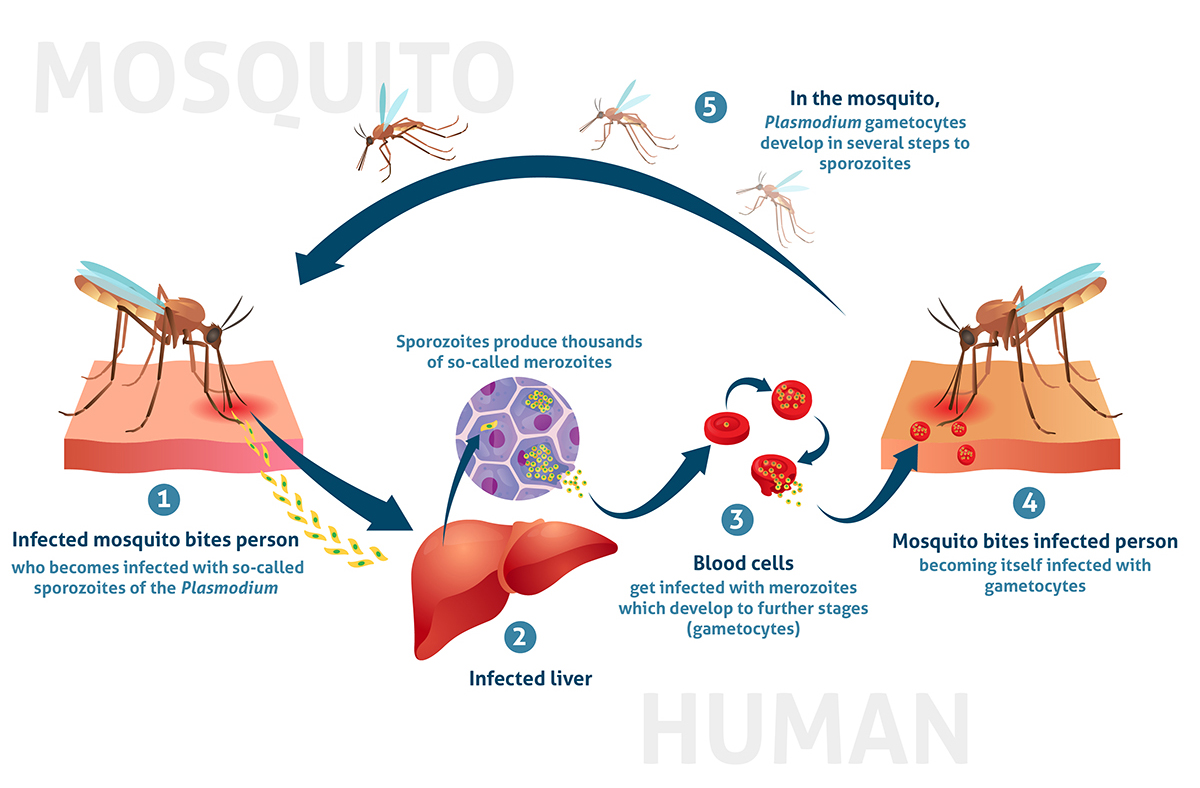

Malaria is caused by microbes of the Plasmodium group. It can cause fever and vomiting and in extreme cases can be fatal: the disease killed nearly 400,000 people in 2018 alone.

Malaria usually spreads when mosquitoes drink the blood of an infected person. This is because the Plasmodium parasites are in the digested blood and can later be transferred to an uninfected person that the mosquito goes on to bite.

But some mosquito bites appear to be more likely to lead to infection than others, says Romain Pigeault at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland.

To investigate, Pigeault and his colleagues exposed the legs of malaria-infected Atlantic canaries (Serinus canaria) to 100 young, hungry Culex pipiens mosquitoes for 3 hours. Each time a mosquito fed on a bird’s leg, the researchers trapped the insect and either froze it immediately in liquid nitrogen or held it, alive, in isolation for a week. They then dissected the digestive tracts of each mosquito to quantify parasite loads.

The birds, meanwhile, were treated and released into large, enriched aviaries where they “live a very good, comfortable life”, Pigeault says.

The researchers discovered similar numbers of Plasmodium parasites inside all of the immediately frozen mosquitoes. In other words, whether a mosquito bit an infected canary 5 minutes or 175 minutes into the 3-hour window, it ended up swallowing a similar number of malaria-causing parasites.

However, when Pigeault and his colleagues dissected the mosquitoes that had been held in isolation for a week, they found dramatic differences. Among these insects, the later-biting mosquitoes – those that bit the canaries towards the end of the 3-hour window – carried many more parasite eggs in their bodies than the early biting mosquitoes. This suggests later-biting mosquitoes are more likely to spread malaria if they go on to bite an uninfected individual.

Although the study was performed in canaries, a similar phenomenon might occur in humans too, says Pigeault.

“Large numbers of mosquitoes biting the same individual can lead to a high infection rate in the later-biting mosquitoes, so it’s really critical to reduce the number of bites per person,” says Pigeault.

As Plasmodium reproduce in mosquito digestive tracts, the later-biting mosquitoes might offer a more favourable environment for parasite reproduction, says Pigeault, although it isn’t completely clear why this is the case.

One idea the team is considering is that when an organism – in this case a canary – is bitten by a mosquito, the host immune system responds in a way that somehow benefits the Plasmodium parasites carried within its blood. When another mosquito then bites the organism, it picks up these boosted parasites, which are better able to thrive and reproduce within the mosquito.

However, the birds showed no visible stress reactions to the bites during the study, Pigeault says, making it unclear whether there really is a significant immune response that might somehow benefit the Plasmodium parasites.

Alternatively, the results might be some sort of evolutionary adaptation within the parasite. It might respond to signals that there are plenty of biting mosquitoes in the environment by increasing its rate of reproduction, because doing so might ensure that it goes through the energy intensive process of reproduction at the moment when it is most likely to pass from host to host, says Pigeault.

Comments

Post a Comment